Calling Jesus an immigrant and a refugee makes some people really angry. Mostly because to many, it sounds like you’re trying to provoke and stir something up. But it’s not a question. It’s his very real biography. Strip away the stained glass cathedrals and the Christmas card images, and you’re left with a Jewish child born into political violence, rushed across a border by terrified parents, and hidden in a foreign land to stay alive. That’s all in the Bible. Just read Matthew 2.

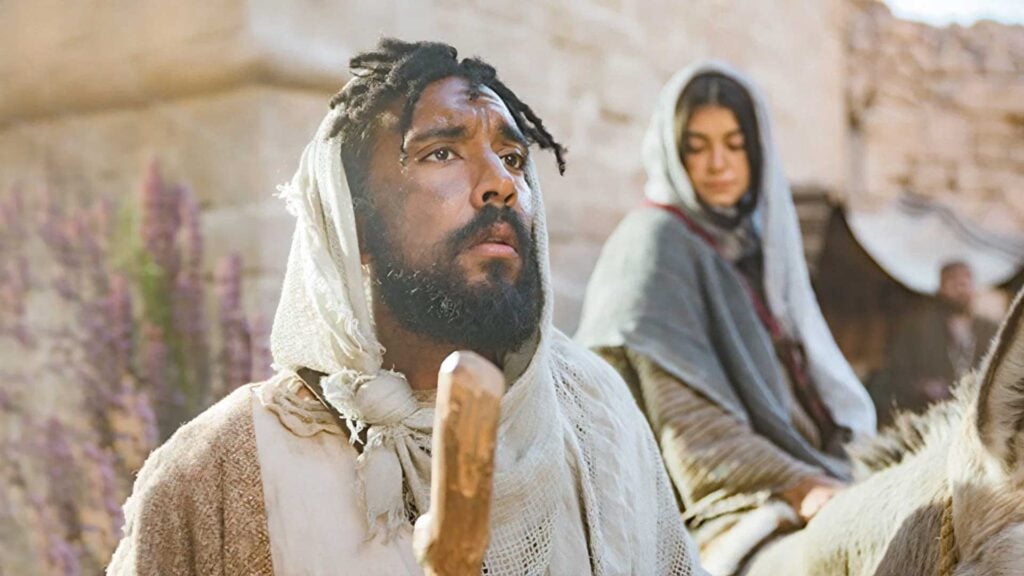

Despite what many might believe, Jesus didn’t enter the world the easy way. His life started out really rough. Right from the beginning. Born in Bethlehem sometime around 4 B.C.E., he didn’t arrive as a ruler or with a huge army to protect him. He arrived as a baby, sleeping where animals ate and slept. Not long after, King Herod became angry after hearing about prophecies of a new king. According to Matthew, Herod ordered every boy under two in Bethlehem and the nearby areas to be killed. And so the soldiers set out to kill babies.

Joseph and Mary were well aware of the threat. Joseph, after being warned in a dream, took his family and fled the country to Egypt. He didn’t leave for work. He left to survive a threat.

By today’s definitions, that’s a refugee and an immigrant, right? The United Nations defines a refugee as someone forced to flee their country because of persecution, war, or violence. A Webster dictionary says a refugee is “one that flees.” Jesus qualifies as a refugee then, right?

The new family stayed in Egypt until King Herod eventually died… which was years later. Even then, their home country wasn’t exactly safe. Herod’s son Archelaus ruled Judea, so Joseph settled the family in Nazareth of Galilee instead. Jesus grew up displaced. First, he was a refugee. Then he was hidden away in a smaller town. So, no, his childhood wasn’t easy at all.

Matthew isn’t subtle about why this matters either. He quotes Hosea: “Out of Egypt I called my son.” That line originally described Israel’s escape from slavery under Moses. Matthew applies it to Jesus here. And not because it sounds poetic and cool, but because Jesus actually reenacts Israel’s story. There was another threatened ruler. Another exit. Another Exile. And another return. Jesus isn’t just part of Israel’s history. He literally carries that story in his bones.

And he’s actually not alone. Scripture is crowded with people on the move. Abraham left home without a GPS. Moses fled Egypt as a wanted man. Rahab defected from Jericho and hid with Israel. Ruth crossed borders with nothing but loyalty and hope, surviving by picking up leftovers in Bethlehem’s fields. David ran from Saul and hid in caves and enemy territory. Hebrews sums it up bluntly: people “wandering about in deserts and mountains, and in dens and caves of the earth.” God seems to work a lot with refugees and immigrants.

Sure, this doesn’t hand you a neat immigration policy. The Bible doesn’t tell governments how many people to admit or how to run border control. It does something more inconvenient. It trains your conscience and tells you to love everyone and help them.

You’re free to debate vetting systems and national limits. You’re not free to sneer at refugees or pretend they’re invisible. Scripture never does that. Not once. God keeps siding with the displaced. Over and over again. Leviticus says, “Love them as yourself, for you were foreigners in Egypt.” Jesus goes further. “I was a stranger, and you invited me in.”

Jesus later chose a life with “no place to lay his head.” That wasn’t accidental either. He literally sent his followers out the same way, without supplies, relying on hospitality from strangers. Welcome them or don’t. That response revealed where a village and a people stood.

Most of us aren’t refugees. That distance makes it easy to ignore the issue. Until you remember this: if you’re in Christ, His story is your story. His flight. His exile. His rejection.

Yes, Jesus was a refugee and an immigrant. And he’s still found among the ones nobody wants today.

RELATED: Does An Ancient Letter From Flavius Josephus Reveal That Jesus Was Real?