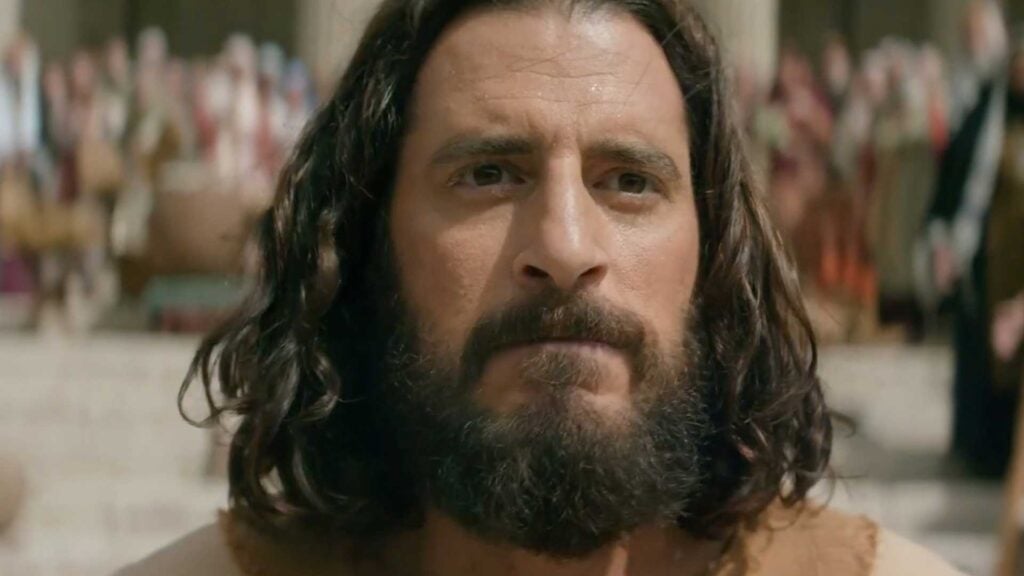

Jesus of Nazareth wasn’t launched by a slick PR team. He was a Jewish preacher executed around AD 30 under Pontius Pilate, a Roman governor historians outside the Bible mention by name. Roman writers like Tacitus and Jewish historian Josephus, writing in the first century, reference him. You can debate divinity. Erasing the man entirely? That’s harder than it sounds.

Here’s the part that tends to surprise people: you don’t need to start with the New Testament at all. You can start with a Jewish historian who didn’t write sermons, didn’t join a church, and still dropped Jesus into his history books. Flavius Josephus reveals that Jesus was a real person and that he did exist.

The “zero evidence” line falls apart

When someone says there’s “zero evidence” for Jesus outside the Bible, what they’re really saying is, “I haven’t seen anything that looks like a modern blog.” Ancient history doesn’t work that way. You don’t get bylines or headshots from 30 AD. You sift through surviving texts, check motives, and notice who mentions Jesus without preaching. Roman and Jewish writers did exactly that. They were people referencing a real man tied to real events.

Flavius Josephus lived close to the action and the time of Jesus

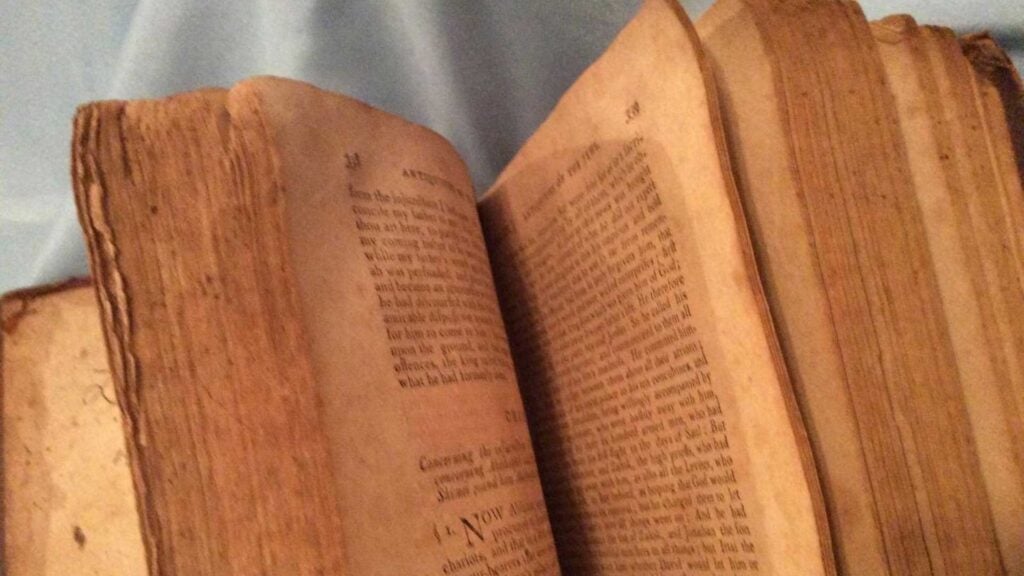

Josephus was born around 37 or 38 AD in Jerusalem, which puts him one generation away from people who remembered Jesus. By his twenties, Flavius Josephus had priestly credentials, political instincts, and a front-row seat to the Jewish revolt that exploded in 66 AD. He surrendered, switched patrons, and kept writing. In his mid-50s, around 93 AD, he finished Antiquities of the Jews.

Josephus did not write his history as Christian propaganda

By AD 71, Josephus had settled in Rome under the watchful eye of Vespasian, writing for Romans who cared about power, order, and what happens when leadership fails. Josephus drops names as cultural markers, not praise. When he does, you’re seeing what people accepted as public knowledge, even stuff they didn’t like admitting.

Josephus mentions Jesus

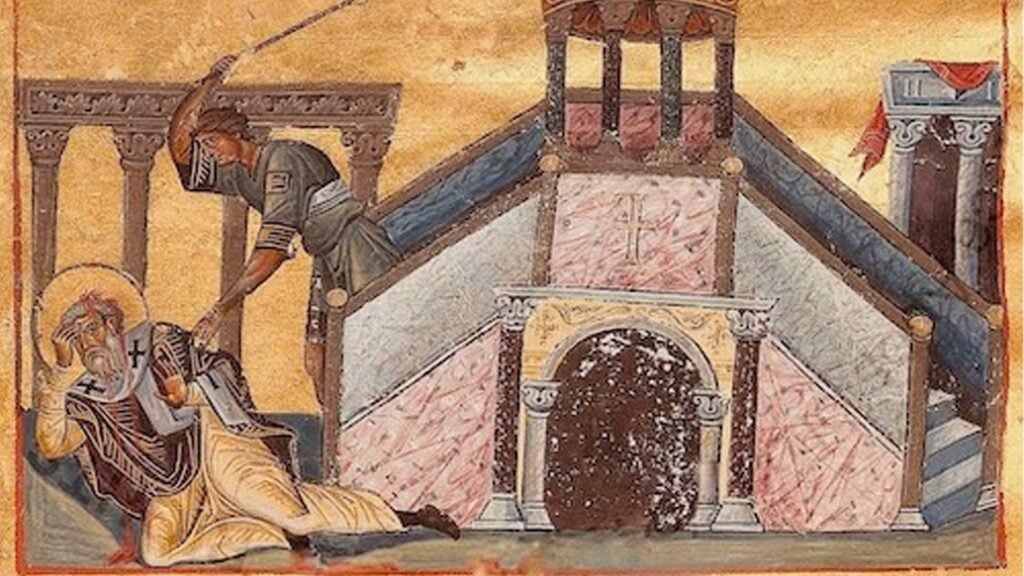

The strongest Josephan reference sits in Antiquities Book 20, Chapter 9, 1, where Josephus talks about the high priest Ananus assembling the Sanhedrin and condemning James. He identifies the James in question as “the brother of Jesus, who was called Christ, whose name was James”.

Josephus doesn’t preach. He doesn’t stop to convince you that Jesus existed. He uses Jesus as a label to clarify which James he means, since “James” and “Jesus” were common names.

The James story also shows how power worked in Jerusalem around AD 62

Josephus places James’ death in the political gap after Porcius Festus died and while Lucceius Albinus traveled to take over, which lets Ananus act before Rome clamps down. Josephus says Ananus “assembled the sanhedrin of judges” and pushed through executions by stoning. People complained. They contacted the king. They even intercepted Albinus to say Ananus had no right to call the council without Roman consent.

King Agrippa removed Ananus after about three months and replaced him with Jesus, the son of Damneus.

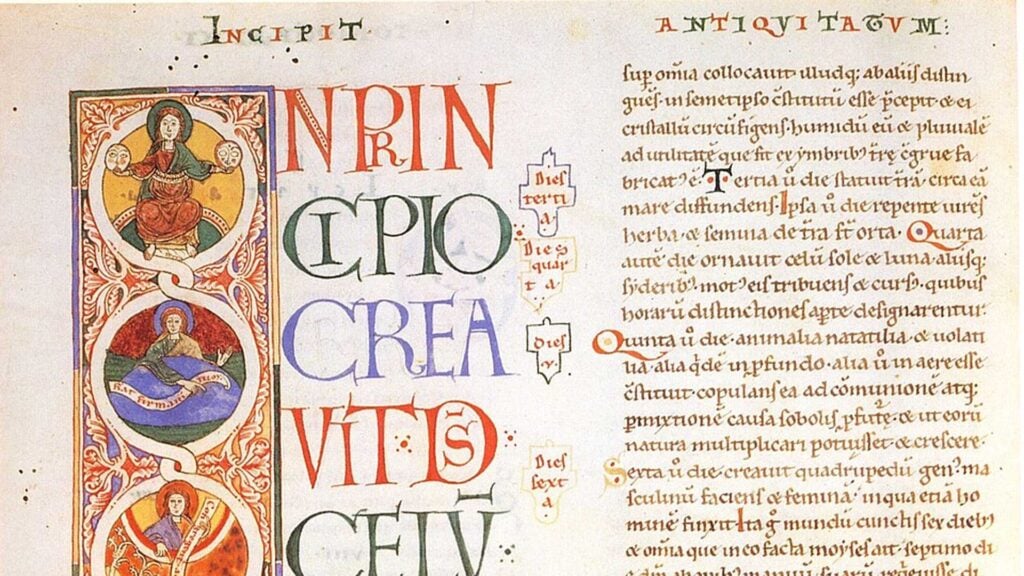

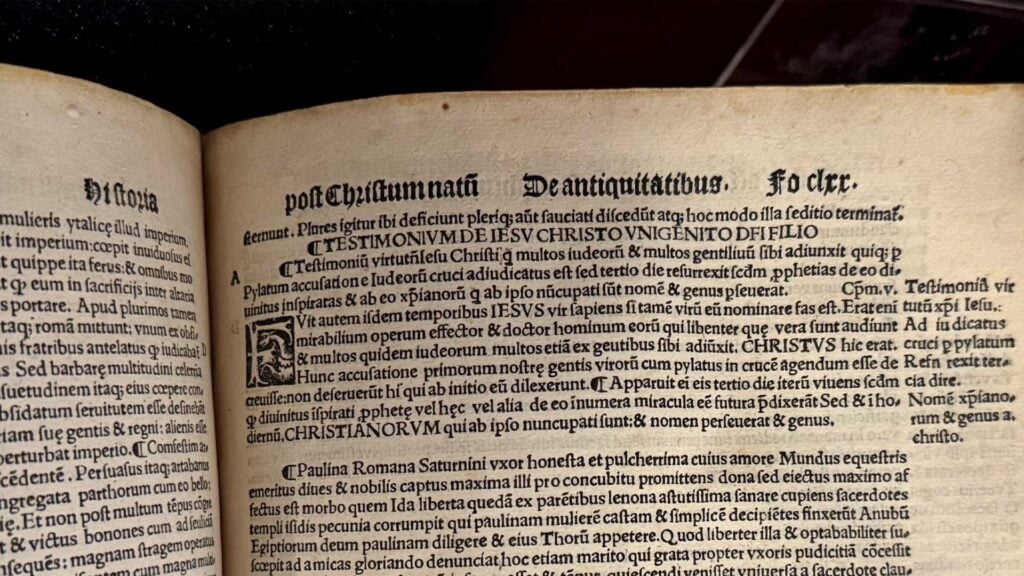

The Testimonium Flavianum

Josephus also mentions Jesus in Antiquities Book 18 in the passage people call the Testimonium Flavianum. The version preserved in Greek manuscripts includes lines that sound like a Christian confession of faith, including language that treats Jesus as the Messiah and hints at resurrection claims.

Most scholars don’t buy that Josephus, a Jew writing for Romans, suddenly started talking like he became a Christian. Instead, many accept a simpler idea: Josephus likely wrote something about Jesus, and later Christian copyists “touched up” parts of it over time. Or maybe they didn’t and he suddenly decided to join the faith.

Even if you strip away the praise, Josephus still talks about Jesus

Once you strip out the lines that sound like worship, the remaining shape looks like something Josephus would write: Jesus as a teacher, a known figure, executed under Pontius Pilate, followed by a movement that kept going. Scholars disagree about the exact wording, because we don’t own Josephus’ original draft.

James D. G. Dunn’s reconstruction captures the kind of plain tone many scholars expect, and it flows into the later James reference in Book 20 without forcing Josephus to confess faith. You don’t need a perfect sentence-by-sentence recovery to see the bigger point. Even a modest reference from Josephus lands outside Christian storytelling.

The manuscript trail explains why people fight over wording

We don’t have surviving manuscripts of Josephus from the first century. The oldest known Greek manuscript that contains the Testimonium comes from the eleventh century, the Ambrosianus 370 (F 128) in Milan. That gap invites debate, because Christian monks copied the texts that survived.

Still, you don’t need to panic and throw everything out. Josephus exists in about 120 Greek manuscripts, with dozens predating the fourteenth century, plus roughly 170 Latin translations, some reaching back to the sixth century. Scholars compare these traditions to catch copyist fingerprints, confirm names, and spot odd insertions.

A non-Christian author (Flavius Josephus) talks about Jesus

Josephus won’t hand you a modern lab report for miracles or resurrection. Ancient history won’t work that way. Josephus does give you something more basic and more useful: an independent, non-Christian author tying early Christian leadership to a historical Jesus.

So if someone tells you Jesus was invented by a group of fishermen and tax collectors, you can now respond with the truth. Jesus existed. History says so. And here’s all the proof you need.

RELATED: Was Jesus Just A Celebrity?